(Text originally published in Nova Express, Volume 4 Issue 1, Summer 1988)

[NOTE: The opinions expressed herein are those of the author. In fact, they are the opinions of the author as of 1988. HE may not even agree with himself these days. It is presented here in the context of its time.]

sexual situations may offend some readers." -- from the dust jacket of Joe Lansdale's The Nightrunners

They're coming for you.

From neon lit streets of darkest Manhattan, where every back alley whispers with the switchblade promise of steel salvation, to the hedonistic paradise of Southern California, where a glittering array of swimming pools gleam like a thousand eyes in the smoggy dusk, to the vast rotting heart of dying England, upon which the last rays of empire have forever set, they're coming for you.

They whisper to you in the still coolness of the Buchandlung, scattered like gleaming shards of shattered glass among the cresting bilge of mass- market horror paperbacks. No third rate hacks, these, stealing their ideas from the far greater thieves that have already ransacked the tombs of Bradbury and King, of Lovecraft and Poe, no pot-boiling tales of My-Son-The-Anti-Christ or The-House-That-Bled. No, they want to tell you far different, far darker tales, soaked in colors of midnight black and dark, dark red.

They come to you, with burning eyes and razor blade smiles, inviting you to join them in their web.

Read one of us, they whisper, just one. We want to teach you what the word "horror" really means. But be careful. Our souls are much darker than you think, and its a long time yet before the dawn.

They're young.

They're gifted.

And they're ready to rock and roll.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you The Splatterpunks.

In the beginning, there was Clive Barker.

Well, that's not strictly true, at least not in the literal sense. When the word "splatterpunk" first came into use (a half comical, half serious reply to the hip arrogance and shrewd calculation that rocketed the word "cyberpunk" to genre wide prominence), there were two works that were regarded as the first true examples of "splatterpunk" horror.

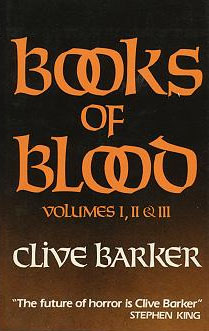

The stories in The Books of Blood were like none the field had ever seen before. They were highly original, powerfully imaginative, and yes, extremely graphic. They were, as the title indicates, much bloodier than any work that had come before.

Infanticide, cannibalism, necrophilia -- all of these features make up prominent plot components in Barker's stories. Yet graphic sex and violence are not the only things that set Barker apart from the horror mainstream. His works were also intensely imaginative and bizarrely original. For example, "In the Hills, the Cities" from Volume I tells of happenings in a remote part of the Yugoslavian countryside, where the citizens of two villages shape themselves into giants in order to engage in ritual combat against the other. It's a richly imagined tale, one so outlandishly unorthodox that no one else would even think of telling it, and one that leaves the reader with a powerful metaphor for the fragility of individuality.

The rest of the stories in the collection displayed the same eclectic and imaginative nature. "The Midnight Meat Train" (Volume I) and "The Skins of the Fathers" (Volume II) both have an eerie and evocatively Lovecraftian feel to them without ever mentioning The Big C or his lesser brethren at the Old Ones Club. "The Yattering and Jack" (Volume I) is a hilarious black comedy about an invisible demon and the nonchalant target of his torments who does not even seem to notice the miseries visited upon him. It is a sly and clever piece, filled with the best characterizations in The Books of Blood, and is the perfect refutation to oft repeated charge that Barker has no sense of humor.

Despite their many ground-breaking features, the stories in The Books of Blood were not without their flaws, perhaps the largest of which was Barker's weakness in characterization. On the whole, Barker's characters were a good deal less interesting than the nightmarish situations he put them in. One really didn't care whether they lived or died, as the blood itself seemed to be more important than the minor matter of whose was spilt. Still, despite their flaws, observers were nearly unanimous in declaring The Books of Blood one of the most important works in horror to come along in years, leading Stephen King to compose his now famous line: "I have seen the future of horror�and its name is Clive Barker."

Though explicit and ground-breaking, one of the things Vampire Junction was not was a terribly good vampire novel. Somtow ends up juggling so many diverse thematic and plot elements that the work ends up in a muddle, ultimately less than the sum of its parts. Because of that, and because Somtow didn't have Barker's deft and icy touch, Vampire Junction slid soundlessly (and not entirely undeservedly) back into the primordial ooze from which it was born.

to Part Two: Splatterpunk: Some Quasi-Arbitrary Definitions

Photo Credits: |

The first was Clive Barker's Books of Blood. Originally brought out as two sets of three in England by Sphere Books (Volumes I-III coming out in 1984, IV-VI following closely in 1985), The Books of Blood sent a shock wave through the collective mind of the American horror intelligentsia. Though (at the time of its publication) its author had not published a single work of horror fiction anywhere in the known world, Barker was almost immediately acclaimed "Britain's answer to Stephen King." Indeed, many reviewers were willing to go beyond and anoint him the genre's new messiah. Fairly heady stuff for someone who had been unknown to the horror field just a year before.

The first was Clive Barker's Books of Blood. Originally brought out as two sets of three in England by Sphere Books (Volumes I-III coming out in 1984, IV-VI following closely in 1985), The Books of Blood sent a shock wave through the collective mind of the American horror intelligentsia. Though (at the time of its publication) its author had not published a single work of horror fiction anywhere in the known world, Barker was almost immediately acclaimed "Britain's answer to Stephen King." Indeed, many reviewers were willing to go beyond and anoint him the genre's new messiah. Fairly heady stuff for someone who had been unknown to the horror field just a year before.

The first three books were the most important, and contained Barker's best short fiction. "Rawhead Rex" (Volume III), perhaps the best story in the collection, tells the tale of a giant rampaging through a English village, eating children -- literally eating children -- and Barker tells of his bloody feasts in graphic detail. While most of the villagers attempt to track down and kill the creature, one man decides to worship it as a god, going so far as to let it "baptize" his mouth and face in a wash of urine. Almost as disturbing is "Dread," a story that tells of one man's obsession to find out what people fear the most -- and then subject them to that fear. We watch his machinations unfold with an almost voyeuristic fascination as he locks a vegetarian in room with no food -- except for one piece of beef.

The first three books were the most important, and contained Barker's best short fiction. "Rawhead Rex" (Volume III), perhaps the best story in the collection, tells the tale of a giant rampaging through a English village, eating children -- literally eating children -- and Barker tells of his bloody feasts in graphic detail. While most of the villagers attempt to track down and kill the creature, one man decides to worship it as a god, going so far as to let it "baptize" his mouth and face in a wash of urine. Almost as disturbing is "Dread," a story that tells of one man's obsession to find out what people fear the most -- and then subject them to that fear. We watch his machinations unfold with an almost voyeuristic fascination as he locks a vegetarian in room with no food -- except for one piece of beef.

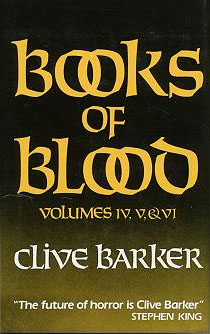

Although there are many more stories in The Books of Blood that are worth a look ["Confessions of a (Pornographer's) Shroud," "Pig Blood Blues"] including several in the second three volumes ("The Age of Desire," "The Body Politic," "The Madonna," "The Last Illusion"), the ones listed above are by far the best and most influential.

Although there are many more stories in The Books of Blood that are worth a look ["Confessions of a (Pornographer's) Shroud," "Pig Blood Blues"] including several in the second three volumes ("The Age of Desire," "The Body Politic," "The Madonna," "The Last Illusion"), the ones listed above are by far the best and most influential.

The second splatterpunk progenitor was the novel Vampire Junction, written by science fiction writer Somtow Sucharitkul under the pseudonym S.P. Somtow. The book tells the complex tale of an immortal teenaged vampire rock star undergoing Jungian psychoanalysis while his therapist's ex-husband and his decadent band of former prep-school buddies try to track him down. Though Somtow's style is a good deal easier to read than (for example) Barry Malzburg's, the thematic complexities (including vampires as Jungian archetypes and the historical relativity of good and evil) and convoluted plot of this novel make it far from light reading.

The second splatterpunk progenitor was the novel Vampire Junction, written by science fiction writer Somtow Sucharitkul under the pseudonym S.P. Somtow. The book tells the complex tale of an immortal teenaged vampire rock star undergoing Jungian psychoanalysis while his therapist's ex-husband and his decadent band of former prep-school buddies try to track him down. Though Somtow's style is a good deal easier to read than (for example) Barry Malzburg's, the thematic complexities (including vampires as Jungian archetypes and the historical relativity of good and evil) and convoluted plot of this novel make it far from light reading.

However, like Barker's early work, Vampire Junction showed Somtow's willingness to take horror to its graphic extreme, mixing violence with explicit (usually perverse) sex to create a shocking and heady concoction. At one point in the novel, Timmy Valentine (the book's vampiric protagonist) finds himself the pedophilic object of the violent and deranged love of the historical Bluebeard, who (in this novel, anyway) stabbed young boys, raped their dying bodies, then cut off their penises and stored them in a large glass jar. In another scene, one of the decadent vampire hunters has his own penis bitten off by a vampiress performing fellatio upon him.

However, like Barker's early work, Vampire Junction showed Somtow's willingness to take horror to its graphic extreme, mixing violence with explicit (usually perverse) sex to create a shocking and heady concoction. At one point in the novel, Timmy Valentine (the book's vampiric protagonist) finds himself the pedophilic object of the violent and deranged love of the historical Bluebeard, who (in this novel, anyway) stabbed young boys, raped their dying bodies, then cut off their penises and stored them in a large glass jar. In another scene, one of the decadent vampire hunters has his own penis bitten off by a vampiress performing fellatio upon him.