|

|

McCammon vows writing days are over

Rejects multi-million-dollar offers

|

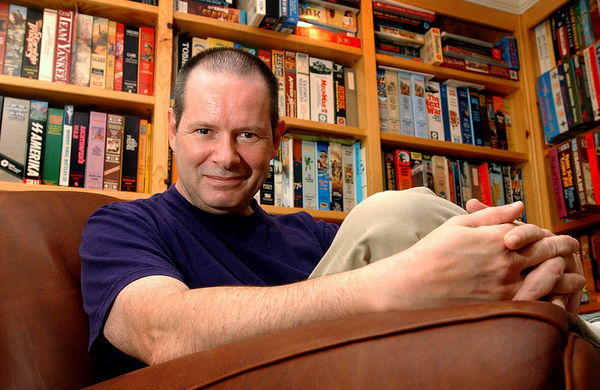

Christine Prichard/Post-Herald

Author

Rick McCammon sits in the converted attic of his Vestavia Hills home. A successful

author in the 1980s and '90s, McCammon says he has now given up writing after

recently releasing his latest work, Speaks the Nightbird, a historical

novel set in colonial North Carolina. McCammon says he is fed up with the

publishing industry. |

The man came from Salt Lake City to get Robert R. McCammon's autograph.

He wants a lot of them, in fact.

Sitting behind a card table at Cahaba Heights' Crosshaven

Books, the Birmingham-born McCammon smiles broadly as the man pulls book

after book out of cardboard storage boxes. The man gently removes foreign

copies of such best-selling McCammon titles as Swan Song,

MINE, and Boy's

Life, and small-press magazines with short stories written by McCammon.

The man also buys a copy of McCammon's most recently released novel, Speaks

the Nightbird, a book he wrote about eight years ago and is just now publishing.

Of course, he signs it.

And, though he's basically churning out signatures, McCammon

— at one time a horror writer whose peers (critically and, in some cases,

financially) included Stephen King, Anne Rice, Dean Koontz, John Saul, Peter

Straub and Clive Barker — is obviously enjoying himself.

"I'm just glad the book is out, so if we had 10 or 100 (people

at the book signing), I was going to be happy about it," McCammon said later.

"It's a little nerve-wracking at first because I haven't done it in a while."

About 10 years, actually. His last published novel, Gone

South, came out in 1992, and while he has written two since, only Speaks

the Nightbird has been published.

The mid-to-late '90s were rough for McCammon, who lives

in Vestavia Hills with his wife, Sally, and 10-year-old daughter, Skye. So

rough, in fact, he has vowed he will not write another book because of the

horrors in the world of mega-publishing. Speaks the Nightbird was published

by River City Publishing, a small, Montgomery-based publisher that used to

be known as Black Belt Press.

It was the headaches he suffered when dealing with New York

publishing houses — which were offering him six- and seven-figure contracts

for Nightbird — that drove him out of the business, he said.

"It's the typical artist's complaint," McCammon said with

a rueful smile over soup and pita bread at lunch. "They didn't treat me with

enough respect."

He felt that, even though the publishing houses were willing

to pay millions for the right to publish his work, they didn't respect it.

He resented being pigeonholed as a horror writer when his last three novels

did not focus on the supernatural at all.

And he chafed at being almost unknown in his hometown and

home state when millions of his books were in print worldwide and he got

fan letters from all over the globe.

"I felt like I'd paid my dues," said McCammon, whose hair

has thinned on top but whose face is still youthful at 50 .

The issue of respect comes up often in the publishing world,

especially in genres such as horror and suspense, said Richard Chizmar, publisher

of Cemetery Dance, a top horror/suspense magazine. Publishers want authors

to churn out the same style of book year after year "because it makes their

job easier," he said. "They can sell it to the same people who bought his

book last year."

That keeps happening "unless you reach that level where

every single book you put out is a No. 1 bestseller," he said.

"They become what we refer to as brand authors," said Carolyn

Newman, publisher of River City. "They fall into that particular genre because

that's the moneymaker, and I can understand that, too. But what we're trying

to do is promote good literature."

"In my opinion, Rick has always been one of our best storytellers,

right up there with King and Koontz," Chizmar said "He gives a little dignity

to the field."

None of McCammon's books ever hit No. 1, although several

showed up on the New York Times bestseller list. And he was handsomely paid

for his writing, earning enough money to live on for the rest of his life.

Yet despite his success, he had to scrap and battle over

each book he wrote, McCammon said.

"I know it's a cliche, but I wanted to be as original as

I could be," he said.

Sally, his wife of 21 years, could see the pressure building

with each new novel.

"I knew that he loved getting started. He loved the research,

and when the writing was going well, he'd come downstairs and just be exuberant

about it," said Sally, a former elementary school teacher who now stays home

fulltime. "Then at the end of each book, he'd just slow down because he didn't

want to finish, didn't want to go through all that again."

McCammon insists he is not ashamed of his horror novels,

although he has pulled the first four — Baal, The Night

Boat, Bethany's Sin, They Thirst — off the market, saying he "grew up as a writer" on

those books and doesn't see them as his best.

To clarify his feelings about his writing days, he mentions

a question fans would often ask when he attended book conventions: What are

you most afraid of?

"I'd always tell them, 'My fear is getting stuck in a box

that I can't get out of,' " he recalled.

In his case, the box was the publishing industry, which

closed in around him in the mid '90s. It took a couple of years for him to

crawl out, but the path was not as liberating as he had hoped. For a few

years afterwards, he suffered from depression and virtually dropped out of

sight.

"Everything seems so hard when you feel that way," McCammon

said.

"For a long time it was a very big mystery about what happened

to him," Chizmar said. "He definitely was the subject of many conversations

and some articles."

Sally said she tried to be encouraging but never told him

to just suck it up and write, which other people in the publishing industry

were saying.

"I just tried to be aware of what he was going through,

but never told him he had to do that again," she said. In fact, I told him,

'You never have to do that again.'"

But McCammon defeated the depression and said every day

is now like "the first day of summer vacation where you've got nothing you

have to do and nowhere you have to be."

He gets up about 11 a.m., a lingering schedule from his

writing days, then spends the next few hours in his office. He's putting

together a fantasy board/card game and is writing the characters and descriptions

for the cards, he said.

A keyboard player, he spent several years building a small

home studio and is writing and recording music.

And he reads, although very little fiction, he said. Instead,

he reads history.

Without writing to demand so much of his time, he can have

lunch with Sally several times a week; he can pick up Skye from her fourth

grade class at a local private school; he can take vacations with his family.

After watching her husband suffer, Sally McCammon said she

enjoys the simplicity of their current life. But if he wants to write again,

she won't stand in his way, she said.

"I believe him when he says, 'I'm not doing this anymore,'

" she said. "But in a year or two, if he says to me, 'I have something I

must tell,' then that's something that he has to feel right about.

"But if he never writes another book, that is great with

me," she said. "Life is grand now and that was a hard time."

From his first novel, 1978's Baal, to Speaks the Nightbird,

McCammon published 13 novels, a short-story collection and many other stories

for magazines, anthologies and other publications. One of his stories, "Nightcrawlers,"

was made into an episode of "The Twilight Zone" in 1985 (directed by William

Friedkin of The Exorcist). None were made into films, although many caught

the interest of Hollywood and some still are under consideration, McCammon

said.

His novels won more awards from the Horror Writers of America

than those of any other horror writer, including King, who approached McCammon

and offered to write the cover blurb for Speaks the Nightbird. King, who

recently announced that he also is giving up the publishing industry, described

the book as "an excellent story full of tension and suspense."

Chizmar ranks himself as a major McCammon fan and said Boy's

Life is one of his favorite books of all time.

"And I've read thousands of books," he said. "It will always

be the one book that I can't wait to read with my son."

McCammon said he was approached by River City Publishing

after reading a segment of Speaks the Nightbird at UAB in 2000. Newman

said an employee of River City heard the reading and came back saying "We

really should pursue this guy." Company officials initially thought, This

is Robert R. McCammon, no way they could afford him, Newman said, but they

went ahead anyway.

"So when we talked to him, he said, 'What I want to see

is this book out there in hardcover,'" she said.

After "many, many monumental telephone calls," a deal was

struck. Money wasn't an issue, he said, getting the book out was.

River City is a far cry from Pocket Books, Viking, Warner

and Scribners, New York publishing companies that had either published or

offered millions for his books in years past. But it was also Speaks the

Nightbird that spawned his career crisis.

A sprawling, 900-page novel, Nightbird veers from McCammon's

usual writing domain.

Instead of exploring the terrifying lands of vampires, baby-stealing

psycho killers, Alabama boys in semi-magical worlds and secret agents who

are also werewolves, Speaks the Nightbird is a historical novel set in

the 1500s on the coast of North Carolina. There is nothing supernatural about

it, although it involves a witch trial.

And the editors at Viking Books — who offered McCammon a

seven-figure contract for it — wanted to change it, he said. Too much.

"They said, "What the hell is this?' " McCammon said. "They

just didn't understand it at all. ... They were basically telling me, 'You

don't know what you're doing.'

"The worst thing that can be done to a writer is make you

think that you can't put a story together," he said. "That's what we do."

It wasn't that he minded being edited, he said, noting that

he trimmed about 200 pages out of Nightbird before River City published

it. But Viking "wanted to turn it into a historical romance" with the main

male character falling in love with the main female character and the pair

riding off happily into the sunset at the end, he said. The editors also

wanted him to ratchet up parts of the book that he believed were minor elements

while chopping out huge sections he thought were central to the story, he

said.

Fed up, the previous years of battles stiffening his spine,

McCammon refused to sign the contract.

"I took my ball and went home," he said with a shrug.

"He felt so strongly about the book," Sally said, "that

when he said that's what he needed to do, I said, 'Then do it. If you don't

feel like you need to sign the contract, then don't.' "

Other companies expressed interest in Nightbird, McCammon

said, but all of those deals fell through, including one case in which the

editors "loved it" but couldn't buy it because the marketing department didn't

know how to sell the book.

Chizmar said he even approached McCammon and offered him

carte blanche for the chance to publish Speaks the Nightbird. He said he

would create a new publishing house name specifically for Nightbird, Chizmar

said, as well as offering him the final say-so on such important items as

cover art, editing and production design.

"I told him he could punch his own ticket around here,"

Chizmar said.

McCammon declined.

After Speaks the Nightbird, McCammon wrote another novel,

The Village, about a Russian theatrical troupe, but it's still sitting

in his home, unpublished. Even if Speaks the Nightbird does well, he said

he's not sure he's interested in publishing The Village.

Newman said River City has already approached him about

publishing The Village and will continue to try to convince him to do so.

And she believes that, once McCammon tests the waters with Speaks the Nightbird,

he'll be willing to go back to writing.

"Once a writer, always a writer," she said. "I think he

has his reservations as to whether or not he wants to be out there in the

public world. But the way I feel about him, yes, he is going to come forth.

He has too much to say."

McCammon acknowledged that he misses the crafting of stories

and the creation of worlds, but said he doesn't miss the days, weeks and

months he would spend researching and writing the novels, sequestered away

from Sally and Skye.

And apparently his daughter doesn't miss those days either.

"Skye came up to me a while ago and said, 'You're not going

to start writing again are you, Dad?'" he said.

|