|

|

From the Archives:

Robert R. McCammon

A veteran of the horror genre has changed directions, after

more than 10 books, with a novel set in the South

By Sam Skaggs

|

"What makes you most afraid?" Robert R. McCammon is often asked.

When he answers, "I'm terrified of confinement," the questioner

naturally thinks of Poe's "The Premature Burial" or of Stephen

King's writer held captive in Misery. Confinement is the perfect

horror writer's fear.

But McCammon means it in a different sense. After 10 novels and a

collection of stories in the horror genre, he has made a sharp turn

with his 12th book, Boy's Life, just published by Pocket

(Fiction Forecasts, May 31). Though it contains elements of the

supernatural, McCammon's latest is a nostalgic, sentimental novel in

which the good end up happy and the bad unhappy in the young

protagonist's fictional Alabama hometown. The Steven evoked by

Boy's Life is Spielberg, not King.

This is also McCammon's first novel set in the South. A lifelong resident

of Birmingham, he once feared the label "Southern writer" as too

confining. During a lunch break from signing books at the recent ABA

convention in Manhattan, McCammon talks about his new-found Southern voice.

"I've reached the point where I can set a novel in the South if I

want, knowing that I don't have to. I've also realized that you don't

necessarily have to use the conventions of Southern writing to get your

point across. I hope these changes have come about because I'm becoming a

better, more confident writer."

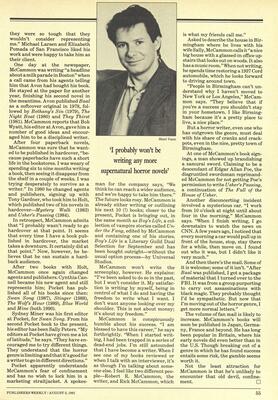

As part of his metamorphosis, McCammon has announced that he "probably

won't be writing any more supernatural horror novels." Asked if

publishers and readers might reposition him as a Southern writer of

the Pat Conroy yarn-spinning school, he says, "They may, and that might

be nice for a short time, but I don't want to stay there. I don't want

to be limited by anyone's pre-conceptions."

McCammon doesn't anticipate resentment from his fans as he takes them

from a familiar genre into new territory. "My real fans believe that

wherever I take them, it will be a good trip. It doesn't have to be

across dark and bloody ground. It can be across green hills."

Is it possible he's experiencing burnout after so many horror novels?

McCammon admits that he "knows all the tricks of writing in the genre,

like a magician who understands where the rabbit really comes from."

But he's restless, not jaded. "I just can't be happy as a one-note,

one-genre writer," he says.

Despite the horror genre's higher profile in the last decade or so,

and despite its greater respectability, McCammon dislikes the

increasing violence found in horror's pages, which he attributes to

the influence of recent Hollywood films.

"In books and movies, horror has moved away from classic psychological

suspense, losing the Hitchcockian touch. Horror stories have traded

grace and character for dumbness influenced by the garbage that

Hollywood throws out as entertainment. It's also a matter of losing,

or discarding, aesthetic distance. Now writers and moviemakers shove

the horror in your face. I don't like that. I think you can do a lot

more with a lot less."

He blames the loss of craftsmanship in horror writing on "more and

more writers who decide to emulate the big, bloody, violent, highly

successful horror novels. These writers want to make money, and they

do, because that kind of book certainly sells.

McCammon says he began to pull back from horror writing a few books ago,

after asking himself, "What am I doing for readers?" Part of his

answer was, "Reality has become so horrific, there's no point in

trying to compete with the evening news." Hence, the kinder, gentler

McCammon horror novel in which a sympathetic protagonist not only survives

the menace but becomes a better person by the end of the story.

Two pages of acknowledgments at the close of Boy's Life

indicate that McCammon, 39, spent a Norman Rockwell-like boyhood—but

one tinged with terror. He lists among his influences Boris Karloff,

Vincent Price, Jungle Jim, Eudora Welty, Famous Monsters of

Filmland, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Howdy Doody, Walt Disney, Captain

America and Bucky, Gene Autry, Roger Corman, Bela Lugosi and Aunt Bea.

He started reading Poe at the age of eight and loved the stories of

the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. Now he feels more

attuned to "the magical world of the fairy tale than to the blatant

brutality of horror." Like many writers, McCammon seeks to incorporate

in his own work "the qualities that made reading and hearing stories

in childhood so enjoyable."

Since he wasn't interested in sports as a boy, he had plenty of time to

spend reading. "I was a loner," he says in a soft Southern voice

so sincere that you wouldn't hesitate to trust him with your money and

maybe even your life. Solitude gave him time to write stories, even at an

early age. Later he majored in journalism at the University of Alabama.

Unable to get a job as a reporter after graduation, he worked first in a

department store and then in the local B. Dalton's, never dreaming that one

day his own books would occupy considerable shelf space there and in

bookstores around the country.

In 1976 he went to work at the Birmingham Post-Herald as a copy

editor. While there, he wrote his first novel, Baal. "I wanted

to sell it [to a publisher], but I didn't know how," he recalls.

"So I looked up agents in Literary Market Place and sent the

manuscript to several in Florida and California. I was afraid to approach

New York agents because I thought they were so tough that they wouldn't

consider representing me." Michael Larsen and Elizabeth Pomada of San

Francisco liked his work and were happy to take him as their client.

One day at the newspaper, McCammon was writing "a headline about a

milk parade in Boston" when a call came from his agents telling him

that Avon had bought his book. He stayed at the paper for another

year, finishing his second novel in the meantime. Avon published

Baal as a softcover original in 1978, followed by Bethany's

Sin (1979), The Night Boat (1980) and They Thirst

(1981). McCammon reports that Bob Wyatt, his editor at Avon, gave him

a number of good ideas and encouraged him to be a disciplined writer.

After four paperback novels, McCammon was sure that he wanted to be

published in hardcover, "because paperbacks have such a short life in

the bookstores. I was weary of spending six to nine months writing a

book, then seeing it disappear from the shelf in a couple of weeks. I

was trying desperately to survive as a writer." In 1980 he changed

agents and publishers, signing up with Michael Larsen and Elizabeth

Pomada, who took him to

Holt, which published two of his novels in hardcover—Mystery

Walk (1983) and Usher's Passing (1984).

In retrospect, McCammon admits that "I probably wasn't ready to go

hardcover at that point. it seems that every time I have a book

published in hardcover, the market takes a downturn. It certainly did

at that point." Now, however, he believes that he can sustain a

hardback audience.

After two books with Holt, McCammon once again changed agents and

publishers. Tony Gardner became his new agent and still represents

him; Pocket has published all of his books since then: Swan

Song (1987), Stinger (1988), The Wolf's Hour (1989),

Blue World and Mine (both 1990).

Sydney Miner was his first editor at Pocket, for Swan Song.

From his second Pocket book to the present, his editor has been Sally

Peters. "My editors at Pocket have given me a lot of latitude," he

says. "They have encouraged me to try different things. They

understand that the horror genre is limiting and that it's good for a

writer to go indifferent directions."

Pocket apparently understands McCammon's fear of confinement and has

no wish to lock him in a marketing straitjacket. A spokesman for the

company says, 'We think he can reach a wider audience, and we're happy

to take him there."

The future looks rosy. McCammon is already either writing or outlining

his next 10 (!) books; closer to the present, Pocket is bringing out,

in the same month as Boy's Life, a collection of vampire

stories called Under the Fang, edited by McCammon and

containing one of his stories. Boy's Life is a Literary Guild

Dual Selection for September and has been bought outright—without

the usual option process—by Universal Studios.

McCammon won't write the screenplay, however. He explains: "I've been

asked to do so in the past, but I won't consider it. My satisfaction

is writing by myself, being in control of what I do and having the

freedom to write what I want. I don't want anyone looking over my

shoulder. This is not about money; it's about my freedom."

McCammon is conspicuously humble about his success. "I am blessed to

have this career," he says forthrightly. "When I started writing, I

had been trapped in a series of dead-end jobs. I'm still astounded

that I have become a writer. When I see one of my books reviewed or

when I talk with an interviewer, it's as though I'm talking about

someone else. I feel like two different people—Robert R. McCammon,

the writer, and Rick McCammon, which is what my friends call me."

Asked to describe the house in Birmingham where he lives with his wife

Sally, McCammon calls it "a nice big house with a glassed-in office

upstairs that looks out on woods. It also has a music room." When not

writing, he spends time restoring a 1937 Cord automobile, which he

looks forward to driving around town.

"People in Birmingham can't understand why I haven't moved to New York

or Los Angeles," McCammon says. "They believe that if you're a

success you shouldn't stay in your hometown. I like Birmingham because it's

a pretty place to live, a nice place."

But a horror writer, even one who has outgrown the genre, must deal

with his share of cranks and crackpots, even in the nice, pretty town

of Birmingham.

At one of McCammon's book signings, a man showed up brandishing a

samurai sword. Claiming to be a descendant of Edgar Allan Poe, the

disgruntled swordsman reprimanded McCammon for not getting Poe's

permission to write Usher's Passing, a continuation of The

Fall of the House of Usher.

Another disconcerting incident involved a mysterious car. "I work from

10 o'clock at night until about four in the morning," McCammon says.

"When I finish writing, I go downstairs to watch the news on CNN. A

few years ago, I noticed that every morning a car would pull up in front of

the house, stop, stay there for a while, then move on. I found out who it

was, but I didn't like it very much."

And then there's the mail. Some of it is welcome; some of it isn't.

"After Baal was published, I got a package of material that I

turned over to the FBI. It was from a group purporting to carry out

assassinations with black magic. They probably thought I'd be sympathetic.

But now that I'm moving out of the horror genre, I get more normal

letters."

The volume of fan mail is likely to increase. McCammon's books will

soon be published in Japan, Germany, France and beyond. He has long

been popular in Britain, where his early novels did even better than

in the U.S. Though breaking out of a genre in which he has found

success entails some risk, the gamble seems worth it.

Not the least attraction for McCammon is that he's unlikely to

encounter that old devil, confinement.

Staggs, author of M.M. II: The Return of Marilyn Monroe, is

finishing a novel about Maria Callas.

|