An Interview with

Robert McCammon

by Rodney Labbe

|

|

Editor's note:

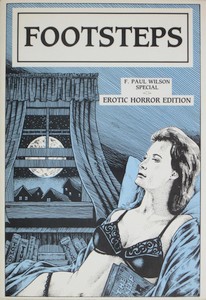

This article appeared in the November 1987 issue of Footsteps, issue

number 8. It is reprinted here with the permission of its author, Rodney

Labbe. Thank you!

The first Robert R. McCammon book I ever read was They Thirst—and although

I was more attracted by the gruesome cover than by author recognition, it

didn't take long for me to realize that McCammon possessed a definite flair

for the supernatural. Plainly put, this Southern Gentleman can conjure up

horrifying images better than any storyteller I know. And yes, that

includes the infamous "Triumvirate of Terror," King, Straub, and

Koontz.

Since 1978, Robert McCammon has written over five best-selling horror

novels, most of them paperback originals. But it wasn't until 1981—and

the publication of They Thirst—that he began to emerge as a critical and

commercial sensation. The hardcover market soon beckoned, and McCammon set

about producing what many consider to be his crowning achievement,

Mystery Walk.

He followed that masterpiece with Usher's Passing, perhaps his most daring

project to date. A modern-day chronicle of Edgar Allan Poe's tragically

flawed Usher clan, it was faithful to its source while showcasing

McCammon's own unique brand of horror. His newest book, Swan Song, is

about to be released—and advance word is that this work will finally

elevate him to superstar status. Well, it's about time! The man's

capacity to frighten seems almost limitless...is it any wonder that he has

the distinction of having sold the first novel he'd ever written? Not even

Steve King can lay claim to that!

I spoke with Rick as he was researching his seventh novel, Stinger.

Outward appearances can be deceiving—his Southern gentility gave little

clue to the nightmares that lurked within. Still, the conversation was

revealing and, above all, fun.

Labbe: Lately more and more critics have been hailing you as a new

master of horror—and the comparisons to King and Straub are inevitable.

What do you see as the fundamental differences between your work and

theirs?

McCammon: First off, I'm very pleased and honored to be included in

the same company as Stephen King and Peter Straub. Both men are tremendous

writers! As for differences, King is an All-American, gusty, gritty

stylist, and Straub is more influenced by classical British authors. My

style is more Southern—though I do sometimes drift afield from my point

of origin. I didn't start out to be a Southern novelist ... it just sort

of happened that way.

Labbe: Have you always been a big fan of horror?

McCammon: Oh yeah, though as I kid I didn't like to watch horror movies.

Instead, I would cut pictures out of Famous Monsters of Filmland and

tape them up all over my room. For some reason, I identified more with the

monsters than with the heroes; maybe because I was never much of a

"joiner." I was a skinny little nerd who didn't know the first

thing about playing football, and, in the South, if you don't play

football, you might as well forget about being popular.

Labbe: Did you ever tune into any of the old TV classics, like Twilight

Zone?

McCammon: I really enjoyed the Twilight Zone, Outer Limits,

Thriller, and some weird thing called Tales of the Whistler.

I especially liked the opening of Tales of the Unknown—where a

woman closed her eyes, then slowly opened them to let out a bloodcurdling

scream right into the camera. That was guaranteed to make me jump under

the bed!

Labbe: When did you make the crossover from horror fan to horror writer?

McCammon: I've been writing short stories and poems and stuff like that

ever since my childhood days, but I never once thought I could become a

writer. I mean ... that somebody might actually pay me for my

stories was just too crazy to believe! Anyway, I was a Journalism major at

the University of Alabama, and I couldn't find a job at a newspaper after

graduation. So I wound up working in the advertising department of a local

store, running proofs of ads up and down escalators all day. It was truly

a dead-end job, and I knew that if I didn't do something fast, I'd be stuck

in it for the rest of my life. That was when I started on my first novel,

Baal, and I worked on it every night. My folks flipped out! I can

still recall my grandfather saying, "Now son, writing books is a fine

hobby, but don't let it distract you from your job at the department

store."

Labbe: You must have been doing something right! Not every novelist

succeeds in selling that first book.

McCammon: Yes, I did sell my first book. Lucky for me! If I hadn't I

might still be running at somebody's heels in a department store! I guess

Baal sold around three hundred thousand copies, which is pretty

good for a first novel. I found an agent through Writer's

Marketplace and sent him the finished manuscript. From there, it went

to Avon.

Labbe: Was there anyone in particular who motivated you?

McCammon: No one, I'm afraid. I've always wanted to say that I had a

mentor, but unfortunately, I didn't. There was one fiction professor in

college who liked my work, but he'd only praise you if your stories were

about trains. If he read my stuff today, his skull would probably blow

open.

Labbe: It is true that you had difficulty breaking into the short story

market?

McCammon: Difficulty is not the word for it. I had absolutely no luck at

all with my short stories ... mainly because they were terrible! At the

time, I thought they were stunning examples of fiction, and that someday I

was going to break into a major magazine. I wrote a lot of stories in

college—and some of them I actually did write by candlelight, after the

electric company had cut off the power to my apartment. Those were the

days when I lived on Krystals and Cokes—suffering artist and all that

crap, ya see. Well, I'm now writing more and more short stories, and I

think—I hope—I'm getting better at them.

Labbe: The "new" Twilight Zone recently adapted your short story

"Nightcrawlers." Was

it faithful to its source?

McCammon: "Nightcrawlers" was on last fall, and I missed it because I was

speaking before a Friends of the Library group in Tennessee. I saw it

later on a VCR, and I thought it was pretty good. It's strange to hear

lines you wrote coming out of the mouths of real-life human beings. There

were a couple of things the TZ people didn't translate from my story

to the screen, but overall they did a very, very fine job. The thing was

intense!

Labbe: How much of your day is devoted to writing? Do you ever have a

problem with discipline?

McCammon: I write every day, from ten at night until four in the morning.

If the book is going smoothly, discipline isn't a problem. There is a

point where a book will either take off on its own, or just sit there like

a stubborn toadfrog.

Labbe: Do you make any sort of outline before starting a project?

McCammon: No, I don't work from an outline. I write a book word by word,

sentence by sentence, page by page. Sometimes I have no idea what's going

to happen ... but I'd much rather operate that way—it's a lot more fun.

Labbe: Aren't there just so many ways in which a writer can present a

horrifying situation or premise?

McCammon: Yes, there are only so many ways to present a particular

premise—but the challenge is to take that premise or situation, skew it,

turn it upside down and inside out and let fly. For example, right now I'm

doing a book called Stinger, and if I gave you a synopsis, you

might say that the plot was old-hat. Yet I don't think Stinger

will be like any horror novel you've ever read. That's because I've put my

own personal style into it—I've taken a time-honored situation and

brought it up to date.

Labbe: What's your definition of horror?

McCammon: Good question—and I don't have an answer! "Horror" can mean

different things to different people. Is horror a car crash and the

smashed bodies lying on the pavement? Is it a corpse with maggots writing

on its face? Is it the sound of kids wailing in a bombed-out building in

Beirut? Or is it the silence between a husband and wife who realize they

don't love one another anymore? I'd say all of those things are pretty

horrible, and that's why I think the term "horror" is both constraining and

universal. I do consider horror fiction to be serious literature, capable

of saying some very penetrating and important things about the human

condition. Just look at the long list of classical authors who have used

the techniques of horror fiction in their work: Charles Dickens, Jules

Verne, H.G. Wells, A. Conan Doyle, Hawthorne, Dante, Milton—it just goes

on and on. So my definition of horror is not necessarily confined to the

supernatural or occult variety; rather, horror can be very quiet and very

real.

Labbe: Do you read much contemporary horror fiction?

McCammon: I do read a lot of contemporary fiction, though not all of it is

horror. While I'm working, I like to read histories and biographies.

The Shining is probably the best horror novel I've ever read, and

some of my other favorites include The Haunting of Hill House,

All Heads Turn When the Hunt Goes By, Crowned Heads,

Interview with the Vampire, and Floating Dragon. The

resurgence of horror fiction today is a fantastic thing—there's just so

much out there, it's staggering!

Labbe: Any advice for the aspiring writers among us?

McCammon: Sit down. Write. And have a place—maybe just a corner of the

room—someplace that you know you'll use for work. Like everything else,

the discipline of writing is a habit. Don't wait to be "inspired," because

you'll probably be waiting forever. Inspiration comes from working day

after day; if you keep at it, sooner or later your craft is going to

develop. And don't be afraid to show your work to people. Don't be

afraid to hear the truth about your material. It might hurt, but you have

to take the punches in order to keep going.

Labbe: How did you feel about the transition from paperback to hardcover?

McCammon: Strange. What I found out when I got into hardcover was that

there are—by far—more readers of paperbacks. Books, for some reason,

are not considered worth the price by the majority of people in this

country. So I learned that, even though it looks great to have a hardback

or two, the largest readership of horror novels is still in paperback.

Labbe: Were you at all inspired by Stephen King's 'Salem's Lot when

writing They Thirst?

McCammon: Yes, I was influenced by 'Salem's Lot. It made me wonder

what I could do with the vampire scenario. I thought: if Steve King can do

a vampire novel on the scale of a small town in New England, I can do one

on the scale of a major city.

Labbe: How long did it take to come up with a final draft?

McCammon: They Thirst involved approximately nine months of actual writing

time, and before that, I worked on it mentally for three or four months. I

researched the novel in Los Angeles, where I spent one of the most horrible

weekends of my life. I stayed in a Mexican hotel and sprained my back and

had to go to an acupuncturist. It was my first trip alone to the West

Coast, and I had enough experiences that weekend to fill up six books!

Labbe: How did you come to develop Mystery Walk?

McCammon: Mystery Walk grew from an incident that took place during my

childhood. My grandfather's house used to have a huge peach orchard

behind it, and he once allowed a travelling evangelist to put up a revival

tent out there. I could hear those wild voices and wailings night after

night, and I drew on those sensations for Mystery Walk.

Labbe: Would you ever consider a sequel to Mystery Walk? Your ending left

that possibility open.

McCammon: I might, at some point, write a sequel, but I've got a lot of

projects planned, and they don't include going back to something I've

already finished. Again, there's the possibility ... I usually try to

leave all of my books a bit open-ended.

Labbe: It was gutsy of you to use Poe in the prologue of Usher's Passing. The

scene between Hudson Usher and Poe could very well have emerged a

self-conscious mess.

McCammon: I knew that might be a very tricky scene to do, but I wanted to

express my feeling that any writer had the defense of curiosity. So I let

Eddie Poe say it for me.

Labbe: What can you tell us about Swan Song, your latest masterpiece?

McCammon: Swan Song takes place after a devastating nuclear holocaust,

and two of its lead characters are a girl named Sue Wanda (Swan) and a

huge, black professional wrestler. I started working on the book four

years ago. It's approximately 800 pages and covers a period of seven years

or so. I'm excited about it. Swan Song is a very violent, graphically

explicit book. I didn't want to pull any punches in describing the

aftermath of a nuclear war. I expect it might be too strong for some

readers.

Labbe: We've heard so much about King and Straub—why not McCammon?

When are we going to see you on an American Express Card commercial?

McCammon: I don't have an American Express Card! I do have a Sears card,

so maybe if those folks called me, I could do an ad for them. But until

the phone rings, I'll be in my office writing!

|